A Nation Under the Influence: Ireland at 100

Centre Culturel Irlandais presents a new exhibition of work by six artists that explores key influences that were already at play in 1922 when Ireland became a Free State, together with the legacy of those that were put in train by its new government. This is an honest spotlight on the maturing of a nation, in the vein of the candid portrait of Dublin painted by Joyce’s Ulysses.

CCI presents a new exhibition of work by six artists that explores key influences that were already at play in 1922 when Ireland became a Free State, together with the legacy of those that were put in train by its new government. This is an honest spotlight on the maturing of a nation, in the vein of the candid portrait of Dublin painted by Joyce’s Ulysses.

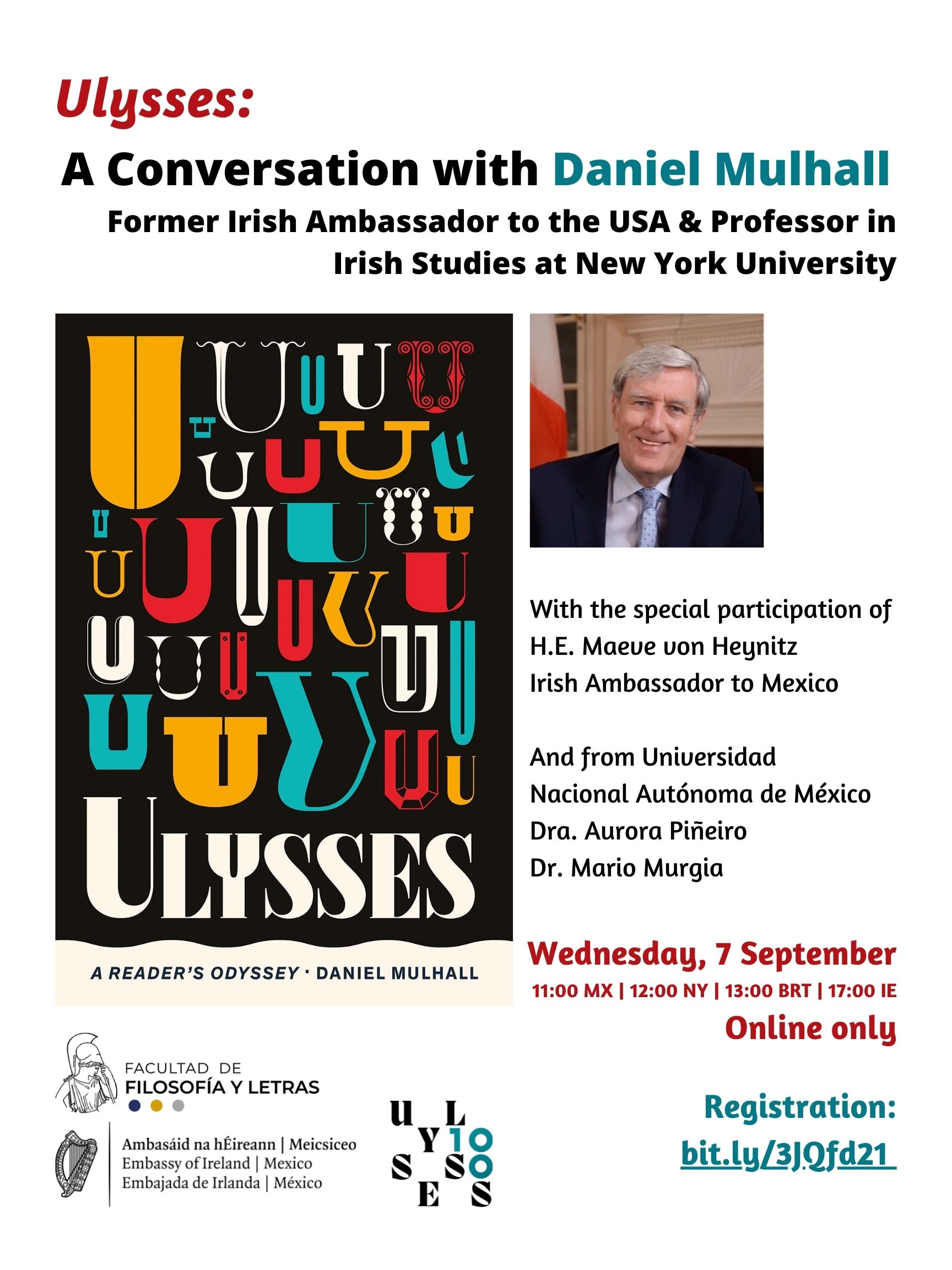

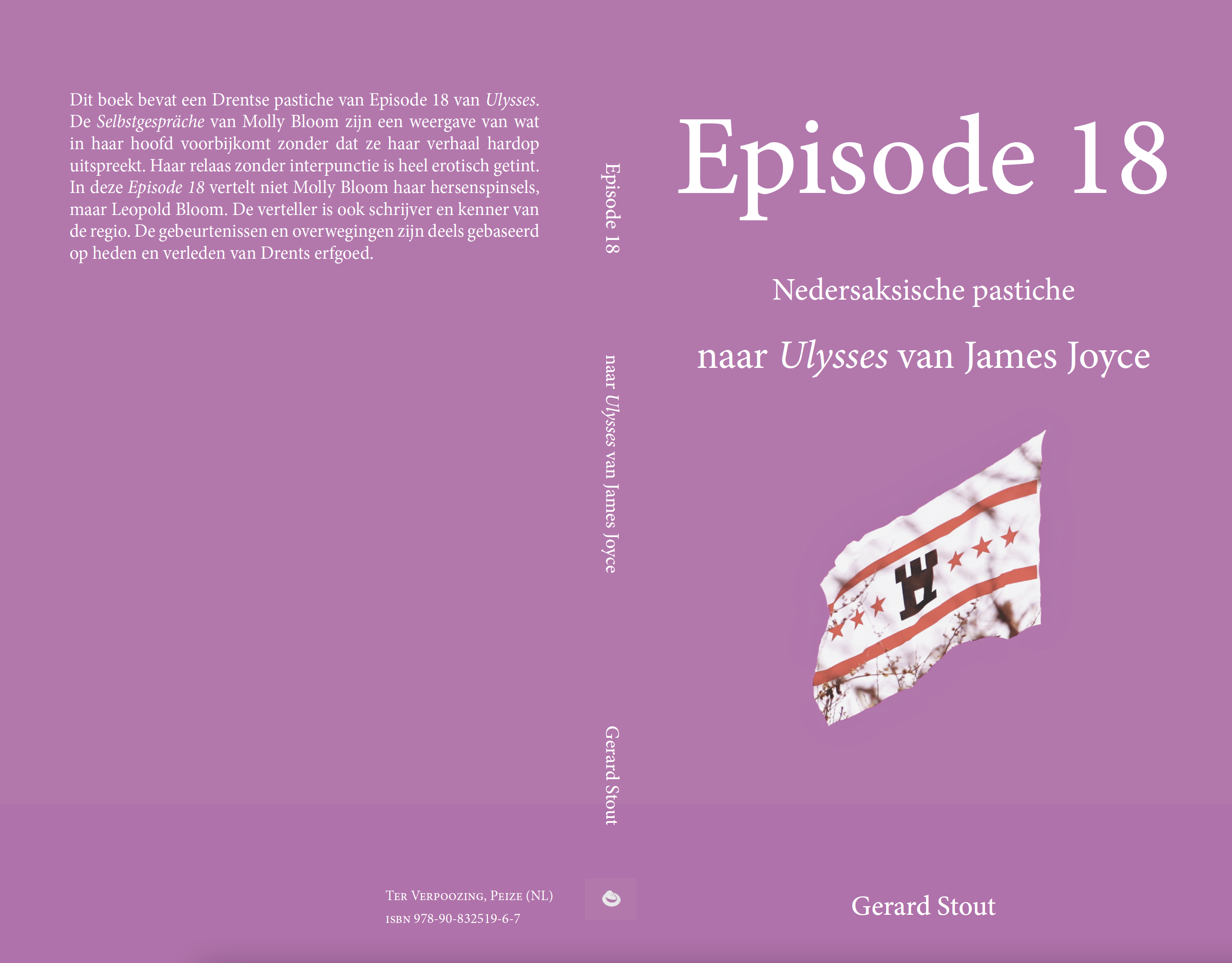

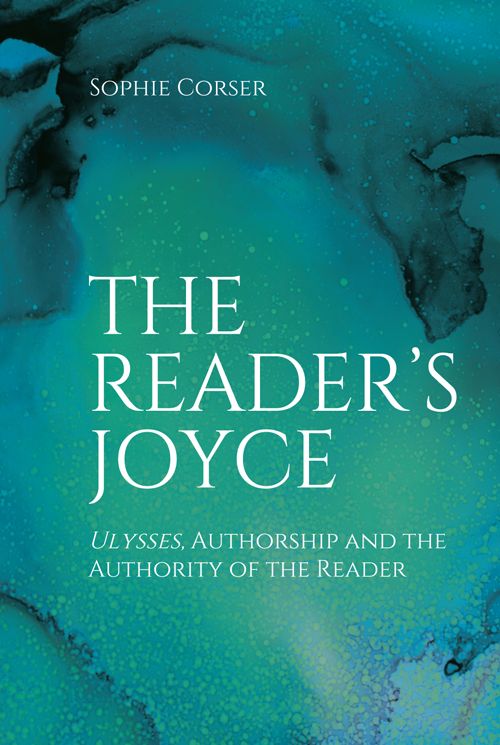

In February 1922, on his 40th birthday, James Joyce finally managed to publish his masterpiece, Ulysses, in Paris, not Dublin, where its ‘obscene’ and ‘anti-Irish’ content was considered too risky! Set eighteen years earlier, on 16 June 1904, this exhilarating roman-fleuve decries what Joyce saw as Irish society’s conservatism, piety, and blinkered nationalism. 1922 is also most importantly the year Ireland finally gained independence in the shape of a Free State. It came however at the cost of partition – six counties of the island remained within the United Kingdom – followed by civil war. Moreover, the new nation that emerged did not put in train the liberal and egalitarian society for which some had fought for; indeed, it can be said that Joyce’s criticisms continued to hold true for a considerable time to come….

This exhibition presents six artists whose work references specific influences — religious, socio-cultural, and political — that Ireland is still dealing with a hundred years after independence and Joyce’s pertinent critique.

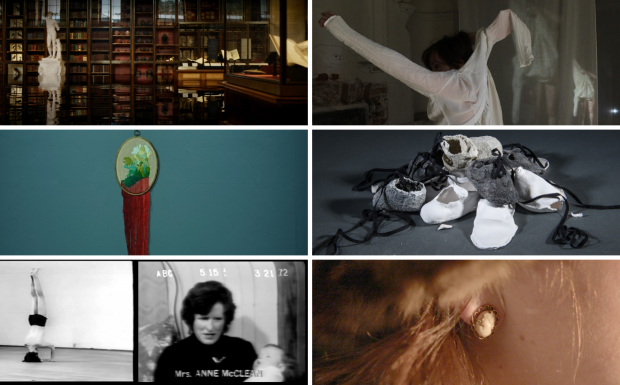

Film artist Ailbhe Ní Bhriain explores the imperialistic mindset that carefully ordered the British Museum’s collections and led to the Irish (and many other cultures) being considered subordinate, quite simply of a different category. Anne Maree Barry’s film is a study of Monto, Dublin’s notorious red-light district that features in Ulysses. Frequented by nationalists and British soldiers alike, it disappeared in 1922 as part of the post-colonial Catholic cleansing of Irish society.

Alison Lowry’s delicate glass sculptures and installations speak of the mental and corporeal vulnerability of those who suffered unspeakably in the many religious-run State institutions of the 20th century.

In her short film, Aine Phillips enacts the difficulty of redress for the victims of this State-Church partnership which still haunts Irish society and politics today.

Jennifer Trouton’s installations investigate the ways in which objects and interiors can reflect and compound national and religious beliefs — in a domestic setting — which she cleverly seeks to subvert.

Partition and political activism are referenced in Mairead McClean’s two film pieces. The first addresses the internment of her father without trial in Long Kesh prison during the early 1970s. The second is a short, humorous look at the goods smuggled into Ireland before and after the creation of the Border.

---

Exhibition curated by Rosetta Beaugendre with Nora Hickey M’Sichili

Organised as part of the CCI’s 6-month Joyce season, marking the centenary of the publication of Ulysses in Paris, and in conjunction with the Department of Foreign Affairs’ Decade of Centenaries programme and the initiative States of Modernity: Forging Ireland in Paris 1922 | 2022.

Find out more: https://www.centreculturelirlandais.com/en/agenda/a-nation-under-the-influence-ireland-at-100