James Joyce’s Ulysses was first published in Paris on 2 February 1922, the author’s fortieth birthday. In 2022, the centenary of the publication of the most renowned novel of the twentieth century is being celebrated worldwide.

Ulysses is now seen as monumental, a staggering work of literary genius. It has acquired the somewhat forbidding aura of a classic, but is also a beloved touchstone for a devoted and enthusiastic audience of readers, translators, writers, and performers around the world.

Yet, its standing on its first appearance was quite different. Joyce’s experimental work was heralded by friends and associates, but also aroused vehemently negative responses. The serialization of Ulysses from 1918 in the American literary journal, The Little Review, elicited nonplussed reactions from readers. It finally ground to a halt in 1920 because early sections of the “Nausicaa” episode were judged to be offensive. Legal proceedings were brought against Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, the courageous editors of The Little Review.

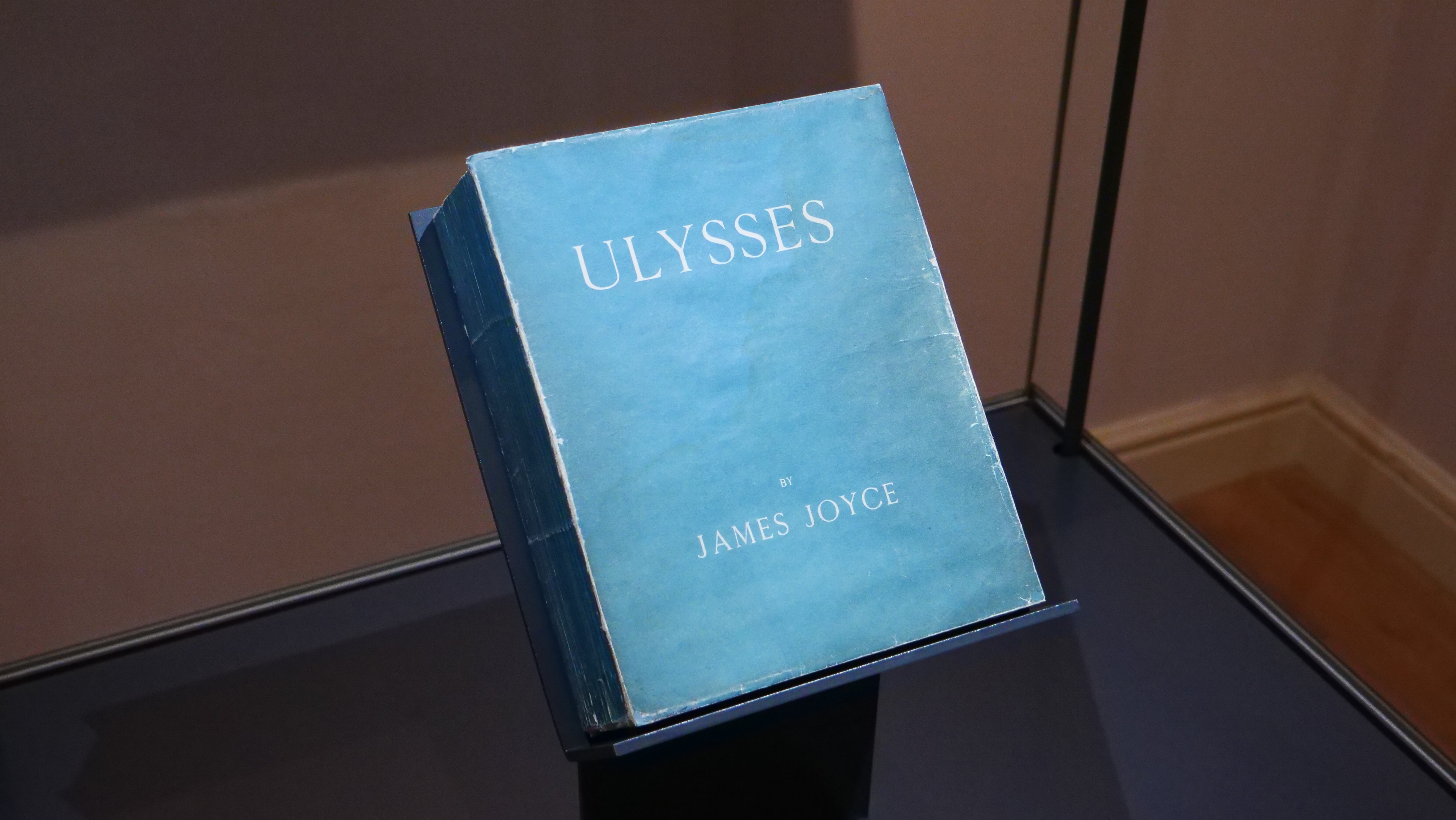

In the wake of the Little Review scandal, attempts to find a publisher in the UK proved futile. Publication in France was ultimately enabled by the enterprising and visionary gesture of Sylvia Beach, an American devotee of radical modern writing, who ran the avant-garde bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, in Paris. Ulysses was published privately under Beach’s imprint. A copy, with its distinctive cover design of a white title on a blue background, the colours of the Greek flag, was placed on display in the window of her bookshop on 2 February 1922 – Copy No. 1 of this edition is now on display at the Museum of Literature Ireland. Initial reviews were admiring but voiced reservations about the obscenity and difficulty of the book in equal measure.

Joyce’s experimental work was heralded by friends and associates, but also aroused vehemently negative responses.

Enigmas and puzzles

Ulysses has long since shed its notoriety as a scandalous book. Readers, however, still struggle with its overwhelming density of allusion and its intricate stylistic experimentation. Joyce presciently quipped that he put enough enigmas and puzzles into Ulysses to keep the professors busy for years. But he envisaged Ulysses as an all-embracing and thoroughly democratic text that anyone could read, from his Aunt Josephine in Dublin to a waiter in a Paris restaurant.

In a letter, Joyce described Ulysses as an epic of the human body. In doing so, he isolated some of the most resonant features of the book. Ulysses takes its bearings from Homer’s Odyssey, which provides it with its key narrative structures of wandering, loss, and return. Joyce relished Odysseus because he was an all-round hero, but also because of his wiliness. Leopold Bloom, Joyce’s Ulysses, is an inimitable creation and the most fully realized character in modern fiction. There is nothing we do not know about him and nothing in turn that he is not interested in.

James Joyce, Dublin 1904 (C.P. Curran, Special Collections, UCD)

An Irish Jew, Bloom is an Everyman figure, but also an outsider who comments on Dublin life from a witty, inquisitive, and sometimes alienated standpoint. In Glasnevin Cemetery, he imagines the dead in conversation with him, “as you are now so once were we”, on O’Connell Bridge he reflects acerbically that he got little thanks from the hungry gulls he just fed, “not even a caw”, meditating on the sea and seafaring, he wonders, “do fish ever get seasick?”, and in a wry meditation on the “worst man in Dublin”, Blazes Boylan, his wife’s lover, he concludes, “He gets the plums, and I the plumstones”. He is a myriadminded, polytropic hero and anti-hero.

Ordinary and everyday

We first encounter Bloom in his home at No. 7 Eccles Street making breakfast for Molly his wife and talking to his cat. Later, he relieves himself in the outdoor privy while reading the journal, Titbits. The action is decidedly ordinary and everyday. But Joyce’s novel is revolutionary in this regard, as it completely expands what fiction can depict. It includes every aspect of lived experience and overrides all taboos about the human body. In Ulysses, people eat and drink, live and die, but they also fart, defecate, menstruate, masturbate, pick their noses, suffer toothache, and have sex.

Ulysses is a one-day novel, set on Dublin on 16 June 1904. It is rooted in a private occasion: Joyce’s first tryst with Nora Barnacle, when they walked out to Ringsend. It everlastingly marks the profane and sublime aspects of human love. But the date is also an unremarkable one that would not have attracted the attention of historians. Continuing the aim of his initial work, Dubliners, Joyce set out to render in profuse and exuberant detail the myriad aspects of life in a modern metropolis. As Edna O’Brien has noted, “no other writer so effulgently and so ravenously recreated a city”. Our attention centres on Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus, but it is also taken up by a host of minor characters, many of whom were real-life figures. Above all, Ulysses provides with us with precise co-ordinates of place and time and maps in infinitesimal detail the streets, buildings, and differing environments of Dublin, from the inner city streets to Sandycove and Dalkey and from Sandymount Strand to the Hill of Howth.

[Bloom] is a myriadminded, polytropic hero and anti-hero.

Ulysses is encyclopaedic, not just because of the material density of its descriptions of Dublin, but also because of its reinvention of narrative and language. Joyce’s letters abound in disparaging comments about Victorian and Edwardian novels by George Moore, Thomas Hardy, and George Gissing. Joyce aimed to be original in Ulysses and to be influenced by no-one. Yet, at the same time, he incorporated a seemingly infinite number of sources and allowed the language he used to be riddled and charged by a multiplicity of other texts. Above all, as Enda O’Brien remarks, “language is the hero and heroine” of Ulysses. Encountering the 18 episodes into which it is divided, she finds, is like reading 18 novels in one.

The excitement of language

Increasingly, too, the excitement of language took over from the pleasures of plot and characterization. The later episodes of Ulysses depart from what Joyce called his “original style” and are prodigiously and dauntingly inventive. In “Sirens”, words melt and language and music mix and fuse; “Oxen of the Sun”, set in the National Maternity Hospital, aligns the gestation of the embryo with the unfurling variety of English literature from the Middle Ages onwards; “Circe”, which takes place in Nighttown, Dublin’s red-light district, is conceived of as a surreal and phantasmagoric drama; and the unpunctuated 8 sentences of “Penelope” convey the equivocal night-time reflections of Molly Mrs Dalloway Bloom, who unweaves the novel and upturns what we have learnt about her and the text overall.

No single summary is sufficient to encapsulate Ulysses. W.B. Yeats saw it as the “work of a heroic mind”, while T.S. Eliot described it as a “book to which we are all indebted and from which none of us can escape”. Virginia Woolf, whose Mrs Dalloway was devised as a counterpart to Ulysses, nonetheless feelingly records her ambivalence about Joyce’s work in her letters: “I look, and sip, and shudder”.

In Station Island, Seamus Heaney describes an encounter with the obstreperous ghost of Joyce in Lough Derg. He advises the Northern Irish poet to free himself of everything and issues the liberating injunction, “Let go, let fly, forget”. This mantra of self-liberation also describes how writers have been licensed to create by Joyce, including Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh, Orhan Pamuk, Amit Chaudhuri, Teju Cole, Patrick McCabe, Zadie Smith, and Colum McCann.

Ulysses is encyclopaedic, not just because of the material density of its descriptions of Dublin, but also because of its reinvention of narrative and language.

Ulysses, not coincidentally, was born in the same year as the Irish Free State. It does not cleave to the past, but looks forward to a future which it helps to invent. Although written against the backdrop of the First World War (1914-1921), it sets out totally to reshape novel while capturing a rounded and uncensored view of reality on a single day in Dublin in 1904. Joyce unabashedly invites readers of all kinds to savour Ulysses in all its endless and dizzying inventiveness.

Fritz Senn has contended that we should envisage the word “Joyce” not as a noun but as a verb. Ulysses also demands to be thought of verbally and dynamically, as it is a text that does not stand still. The centenary of Ulysses will provide many more opportunities for new and continuing readers to discover (or rediscover) this accommodating literary masterpiece and to “Let go, let fly” in as many modes of reading and processes of interpretation as we can come up with.

Anne Fogarty is UCD Professor of James Joyce Studies.

Ulysses, not coincidentally, was born in the same year as the Irish Free State. It does not cleave to the past, but looks forward to a future which it helps to invent.